NOTE: I’m delighted to be once again cohosting a “virtual residency” with my friend and colleague Francois Matarasso on my blog and his. (You can access the previous residencies here: on ethics and on the future of community arts.) Starting 29 September, we’re publishing excerpts from our dialogue on public service employment past, present, and future. Then on Tuesday, 6 October, we’ll host a free Zoom conversation about how to make a new WPA real. It will start at 10 am MDT/5 pm BST (9 am PDT, 11 am CDT, noon EDT—that should be enough to figure out the time if you’re in a different timezone). You need to register in advance for one of the up to 100 slots. When you do, Zoom will send a confirmation email with details. Here’s the link to register.

Download our full dialogue formatted for the UK or for the US (if the links aren’t working, try a different browser or email me at arlenegoldbard@gmail.com and I’ll send you the PDF you want via email). Or if you prefer, you can read an excerpt each day at our blogs.

Here’s the fifth installment.

The USA in the 1970s: CETA

Arlene: Because you talked about the Arts Council, I’ll mention the creation of the National Endowment for the Arts in 1965, which is the equivalent of the Arts Council in Britain. That was driven by Nelson Rockefeller, who had been Governor of New York and later served as US Vice President. He convened under the aegis of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund a blue-ribbon panel on the performing arts and funding. Their report was “The Performing Arts: Problems and Prospects: Rockefeller Panel Report on the Future of Theatre, Dance, Music in America.” They described what they called a culture gap, not between the ignorant unwashed masses and the elite, but a gap in the amount of money that operas, ballet companies, symphony orchestras, major performing arts institutions needed and what they were able to raise from the private sector.

There was a huge terror of state art in the US in the 70s when I was working in Washington monitoring cultural policy. People were still basically saying no, the United States doesn’t have a cultural policy because only totalitarian states have cultural policies; we have freedom, we have the marketplace. So Rockefeller was very, very careful to frame his proposal for federal funding to say private funding should lead. All the grants they gave, except block grants to the states, were matched by private money. The public role is to support the private sector.

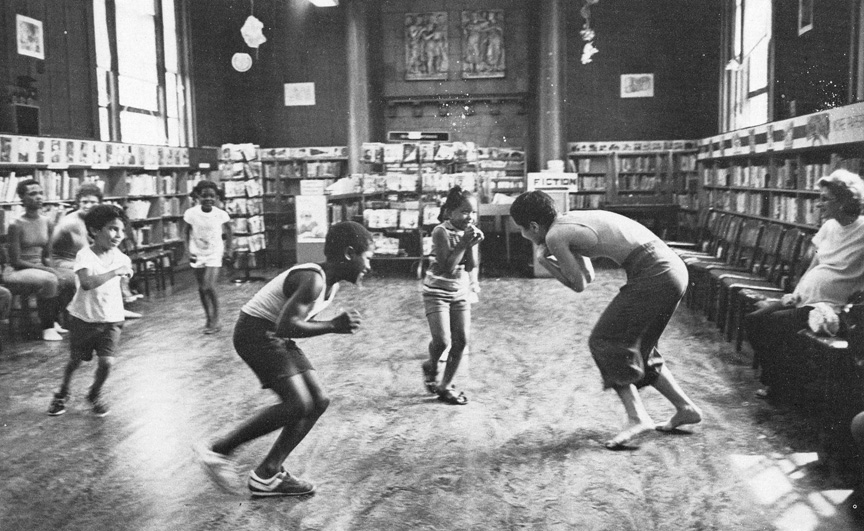

When the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) came along in the mid-70s, it was under the Nixon and Ford administrations that these public service employment initiatives were developed, along with community development block grants and other things. They all had a similar intention: 1968 had seen the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King, lots of civil unrest, lots of violence in the streets of America. They wanted to pour money into the inner cities to address that, and a lot of it was framed in terms of employing youth. So there were these summer youth employment initiatives which had nothing to do with art, per se. Neither did CETA. It was a constellation of public service employment programmes that were triggered when unemployment reached a certain level—much lower than it is now. Two things happened. There were some grants that went directly to municipalities and states, public entities. The other was that non-profit organisations could apply for funds to employ people.

I was in San Francisco then, working for the Neighborhood Arts Program, which was the Arts Commission’s initiative that started with summer unrest—let’s do a workshop for kids—and continues to this day. (I wrote an essay for its 50th anniversary recently.) After I left there, I became an organiser for something called the San Francisco Artworkers’ Coalition, which looked at issues of how funding was allocated and other cultural policies. In the two-year period leading up to the bicentennial of the American Revolution, a lot of artists were outraged at how white the official commemoration was. John D. Rockefeller III had bought up this massive collection of American Art, donated it to the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco. It’s still in the American art wing there. We were furious because it had perhaps one thing by a woman and one thing by a person of colour and it was like 300 pieces of white art that was supposed to represent us all. So a newsletter was started, called the Bicentennial Arts Biweekly and I was an editor of that newsletter. In the issue of December 18, 1974 we wrote, “a queue of 300 unemployed artists each hoping to get one of 24 new arts positions recently made available by the Emergency Employment Act” [a CETA forerunner]. The same thing happened as CETA evolved. In the 1977 issue, we noted that 899 different proposals were being made by nonprofits for the 1500 jobs that were then available.

As these public service jobs started to be allocated, they were made available to open application and everyone was completely gobsmacked by how many people lined up. There was no way to assess before that there were all these artists who wanted to work in community. So the thing kept expanding until Reagan took office at the beginning of 1981. One of the first things he did was cut it off utterly, using those arguments that we talked about before—boondoggles with public money. The Pickle Family Circus was a one-ring circus in San Francisco that had a lot of CETA employees, for example, and that was the kind of thing the right dismissed although the artists were very skilled, and some of them—Bill Irwin and Geoff Hoyle, for instance—went on to become famous. Pretty much everybody in my age group who was involved in community-based artwork—dollars to donuts, 8 out of 10 of them had a CETA job. It was all over the country.

A guy called Eric Reuther, part of a big, famous union family, had contacts at the Department of Labor and got funding to study this phenomenon as an employer of arts people. What happened was just like the WPA: as the project unfolded more and more arts and cultural uses were found for it. There are a few nice reports that sum this up. It was estimated that at the height of the programme, $200 million a year—in mid-1970s dollars, so that’s probably more like $400-500 million now—went to arts-related jobs. It ended up being a huge phenomenon. And unlike the WPA, it wasn’t divided by discipline. There were regional or local boards called prime sponsors that would allocate the funds, creating some kind of process according to general guidelines that could be tweaked. So there was a lot of diversity in in what was supported, but my impression is that the three main things were public art, performing arts and poetry—in New York Bob Holman had the Poetry Mobile and there were a lot of zines. I was a graphic designer in those days and I was running a mimeograph machine, churning out endless flyers. It was all people who one way or another were doing it for what they felt was the public good.

François: Just to be clear, it was a general employment programme, not a dedicated art programme.

Arlene: That’s correct. Public agencies and non-profit organizations hired clerks, janitors… there wasn’t anything that specified or privileged a certain type of work.

François: Why do you think artists did so well with it?

Arlene: The level of demand is a big factor. When they put those first few jobs out and everybody and his brother showed up, they were really surprised. People thought, “Aha, this could be something.” There was a memory of the WPA, which had ended in the 40s, and this is mid-70s, 30 years later. In the Biweekly newsletter, we had interviews with WPA veterans. Nobody had talked to them about this since, because what had intervened is the Red Scare of the 50s, and they were all leftists. We felt like we were doing archaeology, unearthing something that was buried countless years ago, even though it was just 30 years earlier. So we started reading WPA books and felt like we could make this opportunity into something like that. There was a lot of energy for that. It was shocking when it ended so abruptly. We couldn’t imagine that Reagan would be elected.

Reagan had an alliance with something called The Heritage Foundation, which still exists, a right-wing think-tank in Washington. In the run-up to the election and during the time between the election and his takeover of the office they created a document called Mandate for Leadership, a humongous white paper that prioritised eliminating CETA and every other thing that was community-based. This is before things were published online. In the early days, the only way that you could see what was in it was to go to the Heritage Foundation office in Washington. They wouldn’t let you photograph or photocopy it. My partner and I went there and spent the day copying it to share via a community arts newsletter we published. It was shocking. Everything was dismantled overnight. It was a huge blow to the community arts movement in the United States. Up until then, it had been time of rising expectations. There were little bits of money and public programmes and more people were understanding the importance of the work. When then it was cut off, it was profoundly demoralising, and there was a big hiatus in any sort of meaningful or propositional organizing. That’s what I was trying to do. The group that I then became co-director of was called the Neighborhood Arts Programs National Organizing Committee—a couple of years later, we changed the name to the Alliance for Cultural Democracy. If you look at what we put out there—it was just putting things in an envelope and mailing them to people—there’s this attempt to foment self-consciousness as a movement and to propose. But it was really heavy lifting because it was a really demoralizing time.

François: When I became involved in the community arts movement in 1981, that phrase meant something—it did describe itself as a movement. And that said a lot about its sense of confidence and of wishing to change something at a fundamental level. Let me go back a moment because there’s a couple of things you said I want to I want to pick up. I was really struck when you said America doesn’t have a cultural policy. The people saying that are oblivious to the idea that claiming not to have a cultural policy is a cultural policy.

Arlene: Oh, yes. That was my stock-in-trade line: if they’re saying they don’t have one then you can deduce from what they’re doing what it is. It was easy as pie to do that.

François: In Why I Write, George Orwell says much the same thing when he concludes that ‘the opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.’ Of course the American right had no problem with cultural policy, especially in Europe. Here’s what Tony Judt writes in Postwar:

By 1953, at the height of the Cold War, US foreign cultural programs (excluding covert subsidies and private foundations) employed 13,000 people and cost $129 million, much of it spent on the battle for the hearts and minds of the intellectual elite of Western Europe.

It shows the hypocrisy of so much of those attitudes.

Arlene: There should be a better word than hypocrisy. Have you ever heard that word, kakistocracy? It means rule by the least qualified.