I have no reason to believe artists are better or smarter than other people, but I know that artists are often skilled at helping others to see the world more clearly, at focusing awareness and attention. Skilled at perceiving patterns, seeing through the surface of things to deeper meanings, using the connections between things as expressed in the language of symbol, metaphor, and allegory—artists often reveal through depictions, writings, music, and movement what otherwise may be hard to discern.

The Sienese painter Ambrogio Lorenzetti is best-known for a series of six frescoes in that beautiful city’s Palazzo Pubblico, collectively titled the “Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government.” Lorenzetti died of plague in 1348, nearly seven centuries ago, but I often think of these works, visiting their images online to remind myself that civic virtues (and vices) have staying power.

In the above detail from “Bad Government and the Effects of Bad Government on City Life,” a devil named Tyranny presides over the court of bad justice holding a cup of poison. Above his head are Avarice, Pride, and Vainglory. War, Treason, and Fury are at his left; Discord, Fraud, and Cruelty on his right. Justice is powerless, bound up and bereft of her scales.

How would Lorenzetti depict our dystopian electoral system? I doubt even Hieronymous Bosch could do it justice. I haven’t seen contemporary painters take on the challenge, but many, many wordsmiths have been trying to make sense of what we must accept as our current reality, generating an avalanche of often contradictory insights.

We learn most by looking at any subject as if it were not an object but a culture—a fabric of customs, signs and symbols, agreements and relationships—looking without assumption, as if we were seeing it for the first time. What we learn depends how we frame the picture. Those who see our electoral system, however flawed, as just the way things are will focus on playing the game skillfully to win the most votes. In the run-up to the presidential election, the circumstances were so dire and the desire to remove #IMPOTUS from office was so great that we enacted a national agreement to put everything else aside and win. Questions of electoral strategy and tactics were paramount.

To depict this, I might borrow a character who resembles Princess Redfish from Chinese opera, mowing down enemies by fighting with all four limbs at once.

Excepting the impending Senate runoff in Georgia, the election is now over, allowing a new picture to emerge.

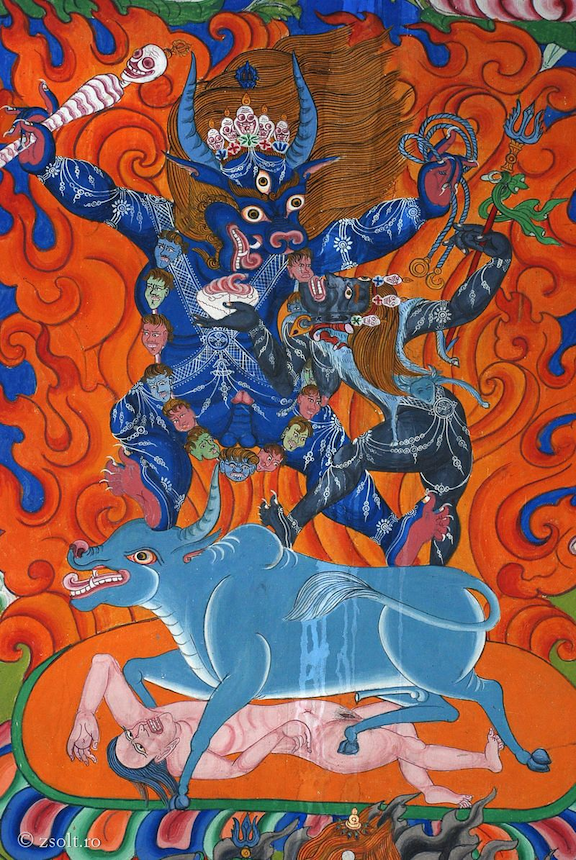

Those like myself who see the system’s flaws as irreparably harmful, as rendering it antithetical to real democracy, might now borrow a demon depiction in a Tibetan thangka to portray a complex engine of appetite and advantage, showing how the electoral system itself—the way we regulate voting, run and fund campaigns, understand competition, and frame winning and losing—is distorting democracy to the breaking point. I don’t think it can be fixed without a complete overhaul as described in part two of this essay, to run on Monday.

I wish more people saw this too. Competing visions of electoral politics and proposed remedies for its shortcomings emerge every day. But they often miss the point: the worst of the problems we experienced with this election are not unique to these times of quadruple pandemic, but intrinsic to the electoral process as it has evolved. The way we do elections weakens the body politic, and heroic measures are needed to heal it.

Consider some of the competing analyses emerging from the last election. Many stories and theories are circulating, but do any of them hold real promise for fixing our wicked electoral problems?

The Republican vote. The single thing everyone seems to agree on is that a surprisingly large number of people voted to re-elect #IMPOTUS. The New York Times recently ran a post-election interview with Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, taking centrist Democrats to task for blaming progressives for Republican gains, pointing out the flaws in those candidates’ campaign strategies. For instance, she singled out Representative Conor Lamb of Pennsylania for failure to use social media effectively. A few days later, the Times‘ daily podcast included Lamb’s response.

The interviewer asked both AOC and Lamb what surprised them about the election, and both responded almost identically, citing the magnitude of votes to re-elect.

Their response is shared by just about everyone I know. From the left side of the aisle, it’s extremely hard to credit that 70 million people voted for someone who doesn’t care if we live or die, who uses the presidency to enrich himself and his family, who colludes with both domestic and foreign villains to destroy democracy—let’s just say who lies nearly every time he opens his mouth and harms life on this planet with nearly every action he takes.

Surprised again? The question I find myself returning to is my own surprise. I was surprised when Reagan was elected in 1980 and again in 1984, just as I was when #IMPOTUS was elected in 2016, then came close to an Electoral College win again this month. The meaning of my surprise seems clear: in each case, I paid more attention to what my friends and allies were feeling about the mood of the electorate than to the electorate itself. You might conclude that I did what some commentators accuse Republicans of doing, stayed inside my bubble of likemindedness focusing on the news that reinforced my assumptions and perceptions. Pollsters did the same, evidently, though some are still trying to tell the story of their failure in ways that soften it, as David A. Graham explains in The Atlantic. However you spin it, what led so many people to a state of post-election surprise was a failure to question our own assumptions and biases, a tendency to seek reinforcement for them rather than test them with countervailing evidence.

And also this: if I had opened my mind to more of the reality I overlooked, how could that have affected the outcome—of the election, the culture, the dilemma? As everyone I know brought everything they had to various forms of organizing and communication this past year, I doubt it would have mattered. It’s important to be aware for its own sake, but awareness isn’t always a remedy.

Their conspiracy and mine. Like most people I know, I find the conspiracy theories of white supremacists (what Yuval Noah Harari in today’s Times calls “Global Cabal” theories) both frightening and laughable. There’s some type of absurdity that links the Republican press conference at a garden center to the QAnon fable of pedophile gangs operating out of pizza parlors. To me, the right-wing frame—public figures living double demonic lives, coded messages in presidential tweets and celebrity gestures—is so silly and far-fetched, I’m barely able to wrap my mind around it even as a thought-experiment.

But it’s no joke that I also believe there’s a conspiracy operating out there, only the one I see is seeking to control politics and finance for its own power and profit. Study the comprehensive and well-funded big business-led efforts since the Seventies to skew public policy toward private profit: decimating protective regulation, denying the truth of climate and energy in the interests of enriching dirty-energy stockholders, privatizing public goods, using taxpayer funds to bail out the banks and corporations that created our financial crises in the first place, driving the polarization of wealth to unbelievable heights. It fits the conspiracy frame of powerful interests working behind the scenes to benefit themselves and cost everyone else both money and freedom. It seems very clear to me that the game is rigged by ruthless people who care more for their own privilege and power than the nation’s well-being.

My conspiracy theory can be documented and proven, not by poring over tweets for hidden messages but by following the money. Who has lobbied for what, where have campaign contributions drawn a direct line to special-interest legislation, who has easily and repeatedly passed the frontier that separates public from private, from the executive suite to government to lobbying and back again? I can’t equate that to QAnon, which Wikipedia defines as a “far-right conspiracy theory alleging that a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles is running a global child sex-trafficking ring and plotting against US President Donald Trump, who is fighting the cabal.” But I can imagine sharing a few seconds of biting laughter with a Q devotee if we happened to be watching some flack for the existing order tell us that government in this country is fair, unbought, and serves all the people equitably.

Disinformation and social media. Within the perpetual post-election analysis (sometimes I wonder if we’ll every talk about anything else), disinformation is high on the list of exacerbating factors. But again, the right means “fake news” (i.e., networks inventing stories to advance their own interests) and the left means Russian bots and far-right big-lie campaigns on social media and white supremacist websites.

I share the pervasive feeling of alarm and impotence in the face of disinformation, particularly the way social media inflames hostility, each side being persuaded to see the other as less than human and fully evil till a whole lot of us tip over into full-fledged demonization. Responding to public pressure, Facebook and Twitter have added more moderation and more flagging or deleting of deceptive posts. From the left, this is perceived as too little too late. Social media must be penalized for making record-breaking profits by servicing Russian disinformation campaigns and offering safe haven to white supremacists. Yet during appearances by the social media giants’ CEOs in Congress earlier this week, both men were attacked by Republicans for overdoing moderation, accused of censoring the right.

In these times, there is no understanding of how things work that does not crash into its equally certain and opposite counterpart. The more effort one puts into understanding, the more complexities emerge.

How to relate to opposite and non-voters. Half the people I take note of say they are seeking meaningful connection with #IMPOTUS voters—the preponderance of white women, the slightly increased showing of Black and Latino voters, the loyalty of many rural voters despite policies that seem to harm them. These people tell me they want to understand what Republican voters need. They seek ways to connect through dialogue, to meet in the middle, or to address those needs without resorting to the usual Republican appeal to fear of the other and trust in autocrats.

The other half see the presidential vote as exposing the entrenched racism of our society, the pliant submissiveness to authority that seems more and more widespread, the greed of those for whom profit always trumps people and planet. They see the challenge as mobilizing the sizeable proportion of eligible voters who fail to vote. They choose not to cater to the disinformed voter, but to seek meaningful, persuasive reasons for potential allies to reject their discouragement or cynicism and take part in the electoral system.

Voter mobilization was uniquely successful in 2020 for both parties, resulting in the most votes ever for both Democratic and Republican presidential candidates. The turnout was the highest since 1900. Around 154 million votes were cast out of an estimated 328 million eligible voters, amounting to about 47 percent of eligible voters and about 67 percent of registered. However you slice it, one-third to one-half of eligible voters left the election to everyone else to decide.

Some of this is down to determined, cynical, and energetic Republican efforts to suppress the liberal and progressive vote by tightening legal restrictions; purging registration rolls; restricting polling places and mail-in voting; spreading disinformation about voting rights and procedures; and even stationing armed guards to challenge people at polling sites. But much more non-voting expresses disappointment, anger, indifference, or the conviction that voting makes no difference.

Future elections. People who focus on the inside baseball of elections point out that the close call this time doesn’t necessarily bode ill for the future if voter-centered organizing continues. Four years from now, commentators such as Steve Phillips have noted, a sizeable number of the oldest white voters who supported #IMPOTUS will no longer be around to vote, while with dedicated organizing, more and more young people and progressive voters of color will have been encouraged to take part. Strictly on the numbers, the margin of Republican defeat can reasonably be expected to grow. So if what we are counting is votes, there’s cause for optimism.

There’s definitely some comfort in imagining that the next win will be easier and fuller, but for ordinary folks who every day experience the ambient mood beyond the beltway, the challenge may be less about voting every two or four years than about finding a way to live together that is less tense and frightening than the default reality to which we have lately become accustomed.

I’ll say it again: each and every one of the problems exhaustively discussed in relation to this election can be ameliorated by looking hard at the culture of electoral politics and committing to a complete overhaul. Seen through a cultural lens—with an artist’s eye for pattern and perspective—it’s easy to spot the inbuilt blockages and obstacles that distort the system. It’s easy to envisage a much better system. It’s essential to use all our gifts of imagination, empathy, and communication to propose a fully dimensional alternative, and to engage a truly national conversation about how to realize it. Please come back on Monday to consider my ideas about how that might best be done—and after you have, please share your own.

Rev Sekou, “Thank You.”

One Response to The Culture of Politics, Part One: The Allegory of Good and Bad Government