“Tikkun” is a Hebrew word usually translated as “repair.” In the phrase “Tikkun Olam,” it has a traditional spiritual meaning associated with Jewish mysticism’s creation story in which the Source of Life shaped the vessels of this world, breathing divine energy into them. The container shattered, unable to hold the infinite light. That left humanity with a prime directive, to repair the vessels so they are capable of holding vast holiness. What people mean by this differs greatly, from the common saying that if all Jews truly observed Shabbos once, redemption would come to the more contemporary sense of Tikkun Olam as social and environmental action to bring about a more just and loving world.

For me, it also has a personal meaning, that the scars of the past can be healed in the present. For instance, many years ago I served as president of a small congregation whose rabbi died suddenly. I threw myself with obsessive fervor into anything that seemed to promise consolation, to help members of the community connect and heal. I sometimes wondered at the intensity of my caring and engagement. It was only later that I realized my father’s sudden death had come at the same age, 47, and having been unable as a child to save my family, decades later this opportunity had been a tikkun for that wound, a chance to help save a very different “family.”

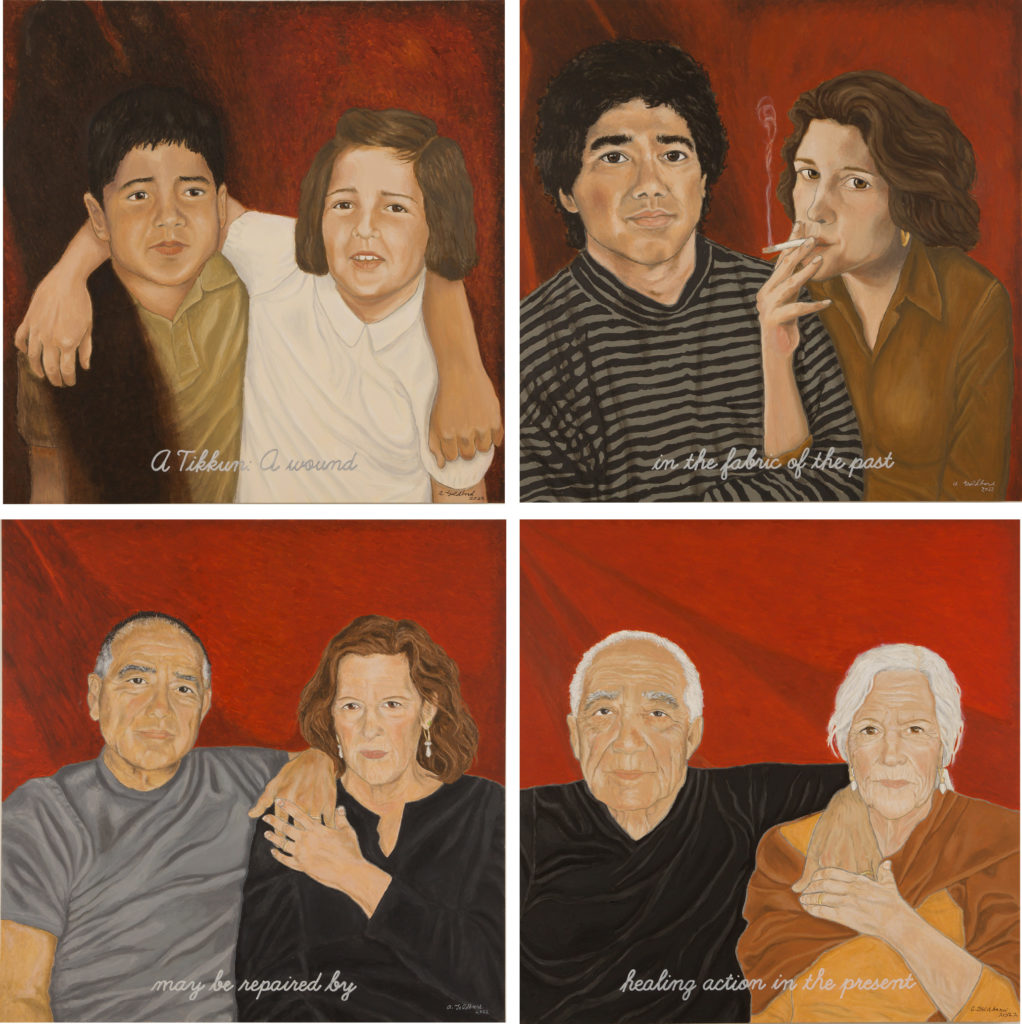

I understand my marriage as another such opportunity. My husband and I came up in very different circumstances, but both of us bear the marks of the used and abused, and for both of us, healing from the past has been a lifelong journey. When we met nearly ten years ago, we discovered our mutual admiration for people whose path is to make something of beauty from the broken pieces we’d be handed; we understood each other in this light. In my new series of paintings entitled “A Tikkun,” I tried to portray that, depicting our presence in each other’s lives long before we actually met, the evolving absence of the dark forces that dogged our childhoods, and the hope of long lives to support the fulfillment of our tikkun.

Read in order, the text on each of the paintings forms a sentence: “A Tikkun: A wound in the fabric of the past may be repaired by healing action in the presence.” Click on the image to see it larger.

This has been a remarkably productive year for me, despite the fact that in the pandemic time, my usual work of speaking, consulting, and writing for others was curtailed. Colleges that had invited me to speak canceled their public events; organizations I’d been advising saw their consulting budgets cut. My income plummeted, but instead of meeting deadlines, I was free to hole up in my studio and do whatever I desired.

Before the spring of 2020, I’d been painting portraits from life, gratefully accepting my friends’ offers to sit, which meant being stationed for hours opposite my easel with only a few feet of distance between us. But once sheltering in place, physical distancing, and masking kicked in, that had to change. I began my search for other subjects.

I started by painting a series of self-portraits (scroll down on my visual art page to see the “Gaia and Shekhina Speak” series). But that couldn’t satisfy me forever. I had to discover what I would love to do as much as I had loved painting real live people.

The answer came fast. For many years, I’d been increasingly disturbed by the disrespect meted out to people whose wisdom comes from lived knowledge rather than credentialed expertise. As an autodidact, I knew from my own experience that both sources of knowledge can be equally valid and deep. I was disturbed by elite educational institutions’ participation in the national rush to convert social goods (such as education) to profit centers. I knew that I hadn’t greatly suffered from my lack of credentials, but too many others had. A question I’d been pondering for years became a mantra: What does it mean to be educated?

Any answer had to start with my own experience. As I began to reflect on it, I saw that my self-directed education had consisted of falling love with one artist, writer, or teacher after another, embracing the beloved’s work, then finding ways to integrate it with my own thinking and actions. I set out of paint a series of portraits of these teachers, choosing eleven people who were no longer alive but persisted in my heart and mind as angels. Once I painted the portraits, I wrote a short memoir to go with each, describing how I encountered and engaged that person’s work. And once I’d written those, I realized that I needed to write about my larger question: What does it mean to be educated?

The result is my forthcoming book, In The Camp of Angels of Freedom: What Does It Mean to be Educated? It will be published by NYU Press in January under the New Village Press imprint, which has published some of my earlier work. I will be sharing more about it as the publication date approaches. For now, I’ll just say it is available for pre-order at the NYU Press site.

If a tikkun is a repair, I must conclude, the instrument—the method, the power, the beauty—of that repair is love.

“Into My Arms” by Nick Cave.