I’m suspicious of nostalgia, even though I’m not immune to it. A glancing reference to the Sixties and I’m off on a magic carpet ride of reminiscence. Despite all of our youthful excesses and errors, I’m as imprinted with that era as a baby duck is with its mama.

The flavor of nostalgia that especially excites my suspicion says life used to be a whole lot better. I get the impulse. I definitely miss things that have been swept away by time. Sometimes I think about how many little craft projects punctuated my days, from embroidering over the rips in thrift shop clothes to macraméing plant hangers. I can’t imagine where all that time came from, but then I remember back before smartphones, being young enough to get by on a few hours sleep, and it makes a kind of sense. But did we used to be kinder, more compassionate, more curious, more disposed to fairness? I’m not so sure.

Still, I’ve been thinking for more than a month about something I read. It was a commentary on that week’s Torah portion from a wonderful group called Rabbis for Human Rights, which is working even more overtime than usual these days, given massive protests in response to the authoritarian crisis in Israel.

In Jewish practice, there is a section of the Hebrew bible assigned to each week. The same stories come around each year in the same sequence, and remarkably, they always reveal something new. On the week in question, it was Ki Tisa, Exodus 30:11-34:35. Like all sacred writings, these can be read on the surface level, or as symbols, even as secrets. To me, they are deep metaphor, evoking ancient tales and ideas to suggest something of value about how we might live today. To pick a random example, I don’t actually think Jonah was swallowed by a giant fish, but in his story, I read something well worth considering about answering or evading the call to help.

The most dramatic moment in Ki Tisa is when Moses, having ascended Mount Sinai to receive the tablets of the law, remains there for so long that doubt grows among the people. They revert to idolatry, forging their jewelry into a golden calf which they then worship.

Writing his commentary, Rabbi Kobi Weiss talks about the need to internalize values rather than looking to an external source of moral authority, about the danger of investing faith in a “transitional object” rather than the inscribing it on our hearts. An external motivation can always be withdrawn, but we can choose instead to rely on deep truths that once understood, cannot be withdrawn from understanding.

Weiss relates this to the situation in Israel. When I read about Israeli politics, in which an ego-mad figure attempts to destroy democracy and liberal values merely to inflate his own power, I can’t help thinking of the United States. Consider this excerpt:

“We face challenging times. Our immediate attention is focused on the public struggle for Jewish and Democratic nature of our country. However, while examining from a wide range of perspectives, and by looking at it from above, beyond the here and now, the destiny of our entire civilization is at stake. We live in a period characterized by loss of shame. Elected public officials lie and manipulate without even a hint of shame…. According to ‘Orchot Tzaddikim,’ ‘The one who shames says: what have I done? So and So did the same… He sins the many, because in such a way his own sin will appear lightly to the eyes of the public, because there will no longer be shame in the sin.’”

There is truth rather than nostalgia in observing that “we live in a period characterized by loss of shame.” Not that those who came before us were never shameless: the creators of manifest destiny, the defenders of slavery, the McCarthyites and so many more make that abundantly true.

But the ultra-extreme loss of shame in public life seems new. Two examples pop instantly to mind. First, the egregious Marjorie Taylor Greene tweeting about her hero Jack Teixeira (who exposed sensitive information that could harm the war effort in Ukraine simply to impress his friends on a Discord gaming server) that he “was “white, male, christian, and antiwar. That makes him an enemy to the Biden regime.” Second, yesterday’s Washington Post story about the repugnant Ron deSantis, who just after law school volunteered for duty at Guantanamo where he distinguished himself by providing the legal rationale for the painful and humiliating force-feeding of prisoners held without charges, using a hose attached to the men’s noses. Pundits doubt this will hurt his chances of running for the Republican presidential nomination.

Weiss goes on to say of the Israeli situation he describes, “This is a damage that goes far beyond the political debate, it is not only about the nature of the country, it’s about the nature of the entire humanity. Such phenomena don’t stop at the borders of a country. In general, it seems that the heroes of our culture, from the celebrities of reality shows in the industrial channels to the elected politicians—they receive the voices of the public and of the citizens exactly for their shameless and immoral activities. Choosing them, even when it is done unconsciously, gives out legitimacy to act immorally.”

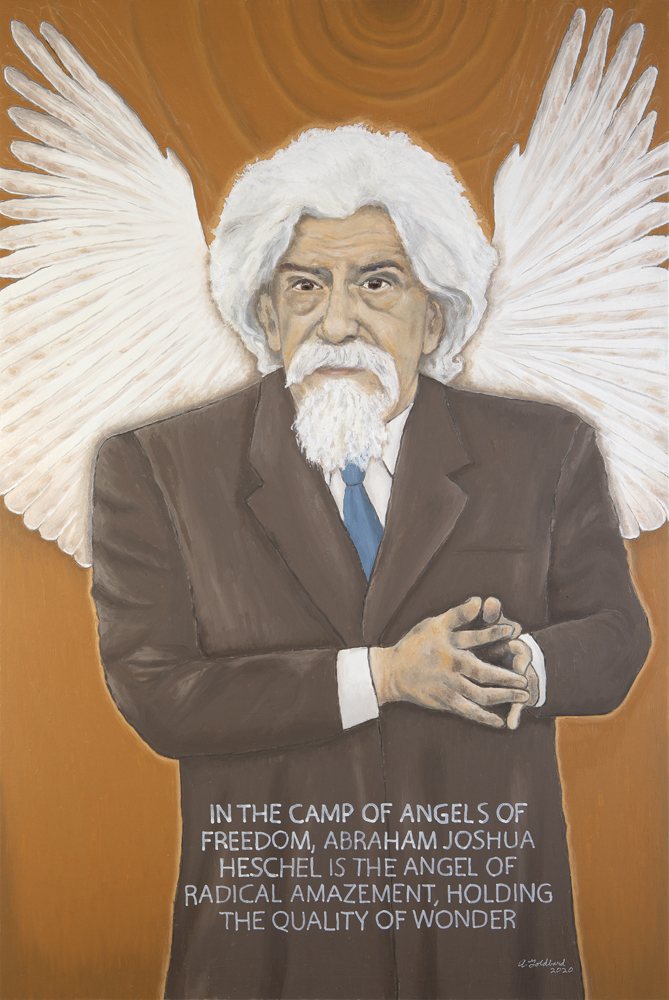

I’d like to have something clever to offer as the antidote to the loss of shame, but only one thing comes to mind, the critical importance of not allowing ourselves to become inured to shamelessness. Of not saying, “I’m not surprised” and turning away. Of not succumbing to the deep fatigue that sets in when the loss of shame spreads and becomes even more appalling. I take my guidance here from Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, one of the “angels” in my new book, who said this:

There is an evil which most of us condone and are even guilty of: indifference to evil. We remain neutral, impartial, and not easily moved by the wrongs done unto other people. Indifference to evil is more insidious than evil itself; it is more universal, more contagious, more dangerous. A silent justification, it makes possible an evil erupting as an exception becoming the rule and being in turn accepted.

“Shame, Shame, Shame” by Jimmy Reed.

Order my new book: In The Camp of Angels of Freedom: What Does It Mean to Be Educated?